What Percent of Turners Babies Make It After 2nd Trimester of Pregnancy

- Inquiry commodity

- Open Access

- Published:

Lack of consensus in the selection of termination of pregnancy for Turner syndrome in France

BMC Health Services Research volume 19, Article number:994 (2019) Cite this commodity

Abstruse

Groundwork

The observed charge per unit of termination of pregnancy (Meridian) for Turner syndrome varies worldwide and even within countries. In this vignette study we quantified agreement among x multidisciplinary prenatal diagnosis centers in Paris.

Methods

We submitted online iii cases of Turner syndrome (increased nuchal translucency, normal ultrasound, aortic coarctation) to fetal medicine experts: i obstetrician, one pediatrician and one geneticist in each of the ten Parisian centers. Each case was presented in the grade of a progressive clinical history with conditional links dependent upon responses. The background to each case was provided, forth with the medical history of the parents and the counseling they got from medical staff. The experts indicated online whether or not they would take the parents' request for Acme. We assessed the percentage of agreement for credence or refusal of Tiptop. We also used a multilevel logistic regression model to evaluate differences among obstetrician-gynecologists, pediatricians and cytogeneticists.

Results

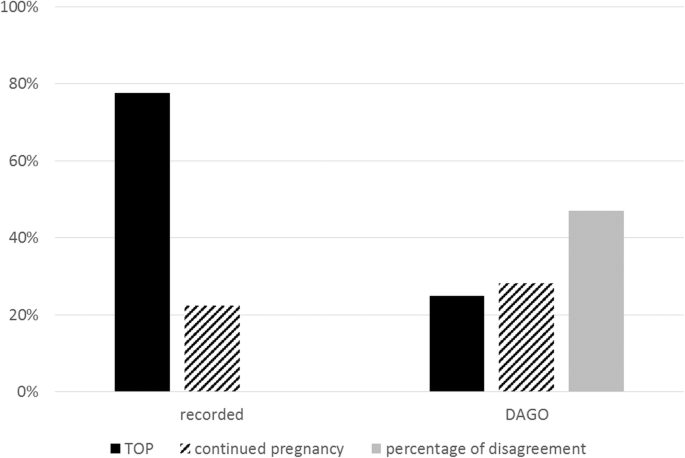

Overall agreement among the experts to accept or refuse Meridian was, respectively, 25 and 28%. The percentage of disagreement was 47%. The percent of agreement to accept TOP was 33, 8 and 33% for obstetrician-gynecologists, pediatricians and cytogeneticists, respectively. The respective percentages of agreement to refuse Height were 19, 47 and 26%.

Decision

Our results bear witness the lack of consensus with regard to decisions related to termination of pregnancy for Turner Syndrome. This lack of consensus in plow underscores the importance of multidisciplinary management of these pregnancies in specialized fetal medicine centers.

Background

Turner syndrome affects 1/2500 of female newborns [1], ie, approximately ane/5000 of all live births. Most fetuses with a 45,X karyotype die in utero and it is estimated that only 1% of fetuses with monosomy X are viable, whence the relatively low prevalence of Turner syndrome [1]. Turner syndrome is acquired past complete or fractional monosomy for the 10 chromosome: half of the patients have a 45,10 karyotype; the remainder are mosaics with a 45,X jail cell line and some have a structurally abnormal 10 (ring X chromosome). Phenotypic expression is variable and depends on the chromosomal formula. Women with mosaicism generally have less severe impairment and an fantabulous prognosis regarding intelligence, whereas women with ring 10 chromosome have a guarded prognosis concerning cerebral impairment. Growth brake is well-nigh always present and results in an adult stature 20 cm beneath the reference population mean [2, 3], but is partially ameliorated by growth hormone therapy [4,5,six,7]. Intellectual ability may depend on hearing impairment, which ranges from hypoacusis to deafness [eight,9,x]. Overall, cognitive deficits are seen in 6 to 10% of patients, who need special schooling [11]. Quality of life during boyhood depends on the brunt of medical follow-up (in the instance of cardiopathy, machine-immune disease, etc) and consecration of puberty [12,13,14,15,16]. Infertility is nigh always present. Quality of life and long-term prognosis depend on the associated conditions [11, 17, 18]: cardiopathy (aortic coarctation in 5 to 10% of cases, bicuspid aortic valves in fifteen%), hypothyroidism in 30% of cases [19, 20], renal anomalies (30–40%) [16]. Long term, Turner syndrome patients have higher morbidity and mortality than the general population because they are at greater hazard of hypertension, obesity and osteoporosis [21,22,23].

Turner syndrome tin exist diagnosed in utero from the showtime trimester when there is an increased nuchal translucency or lymphedema (Bonnevie-Ullrich syndrome) or later when there is a prenatal warning sign. Its prenatal discovery may also exist fortuitous when karyotyping is done for other reasons, commonly when outset-trimester serum marker levels betoken increased hazard of trisomy 21. Prevalence of prenatal detection of Turner syndrome is low and variable over time – from one/300 in the 1980'due south to effectually 30% nowadays [1, 24]. The advent of noninvasive prenatal diagnosis, the indications of which are increasingly broad, too increases the frequency of fortuitous detection of gonosomal abnormalities.

Elective Meridian is performed in 54 to 100% of cases of Turner syndrome in Europe and Northward America, despite the depression gamble of intellectual deficit and absenteeism of mental retardation [25,26,27,28]. Legislation on Summit differs among countries in terms of the number and qualification of specialists in charge with affirming the serious and incurable nature of the fetal disease, the maximum term at which TOP tin be performed, and the legal time for reflection between when the parents are told of fetal disease and TOP [29]. In France, fetal diseases are managed in multidisciplinary prenatal diagnosis centers (PDCs), which help medical teams and parents in analysis, decision making, and pregnancy follow-up when a malformation or fetal anomaly is suspected and when there is a genetical transmission of a illness (article 2131–10 of the Public Health Lawmaking). When there is a loftier probability that the unborn child has a particularly severe condition deemed incurable at the time of diagnosis, the role of the PDCs is to certify this (article 2231–1 of the Public Health Code). This opens the way, should the parents wish, to Height for medical reasons. Different other European countries, in France there is no time limit on when TOP can be performed. There is a mandatory 7-day menstruum for parents to think over their decision between diagnosis of a astringent affliction and Peak. The astringent and incurable nature of the fetal affliction must be certified by two specialists of a PDC: if possible, one specialist of the disease the fetus appears to have and one obstetrics specialist (article Fifty.2213–1 of the Public Health Lawmaking) [30]. Access to elective Superlative for Turner syndrome is subject to numerous ethical tensions. In the EUROCAT database [28, 31], which collects information on congenital malformations in Europe, the rate of elective Meridian for gonosomal abnormalities varies considerably among countries, fifty-fifty when the laws governing Pinnacle are similar [25]. At that place is as well variability among PDCs within a given country [26, 32]. All the same, reasons for this observed variability are unclear and literature has not yet been explored if this deviation is due to the profession of the * PCDs staff members, to local laws upon Tiptop or severity of antenatal signs. Neither has the variability of the decisions been quantified with precision regards to the decision for TOP. Overall rates of TOP hence compare heterogeneous prenatal situations. Indeed, studies compare overall rates of TOP for Turner syndrome [25, 27, 28]: they do not distinguish which signs led to prenatal diagnosis. Both physicians implicated in the controlling process and patients have unlike characteristics. Quantification and noesis of the reasons in different approaches among PDCs could influence their system, including the way the information is given to patients' and decisions to perform invasive procedures.

Our aim was therefore to study the agreement to accept or not parents' demand of TOP for Turner syndrome amid:

-

several PDCs in the Paris–Île de French republic region in standardized clinical cases presented in the form of a vignette.

-

different professionals working in a PDC.

Methods

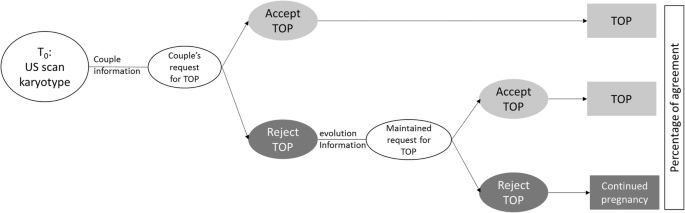

We conducted a survey called DAGO (antenatal diagnosis of gonosomal abnormalities) of practices in PDCs in the Paris–Île de French republic region. 3 online vignettes derived from real-life clinical cases were prepared and approved by a scientific committee composed of 4 obstetrician-gynecologists (AB, OA, MH, VT), an endocrinologist-pediatrician (CB) and two cytogeneticists (Air conditioning, Air conditioning): Turner syndrome with nuchal translucency of 7 mm in the first trimester; Turner syndrome with no ultrasound sign (discovered on amniocentesis washed for an increased risk of Downward syndrome estimated on first trimester markers); Turner syndrome discovered in the third trimester because of aortic coarctation. Each case was presented in the form of a progressive clinical history with conditional links dependent upon responses. The background to each case was provided, along with the medical history of the parents, the reason for antenatal diagnosis, the invasive examination that led to karyotyping, the result of the karyotyping, the information given to the parents, and ultrasound findings before and after the invasive examination. Psychological follow-upwardly was routinely proposed to parents, who saw a pediatric endocrinologist earlier taking whatsoever decision regarding the pregnancy. The information on the prognosis given to the parents was that on the patient information canvass bachelor online at Orphanet (http://www.orpha.internet/). After receiving multidisciplinary data, parents decided to formulate a asking for constituent TOP, and experts were and then asked whether or not they would grant this request (cf Fig. 1).

Online presentation of clinical cases (vignettes). TOP: termination of pregnancy

Depending on the online respondent'southward answer, the experts who would accept TOP were directed to the next clinical instance, whereas the experts who refused TOP continued with the same clinical case. A report on clinical progression indicated the psychological progression of the parents, the ultrasound findings and how they changed, appointments with other specialists, or new appointments with the pediatric endocrinologist. The parents then requested TOP again, despite the proposed medical and psychological back up. Nosotros then asked the experts who had initially refused TOP whether they would take accepted information technology in this context. Nosotros present the percentages of agreement regarding the last conclusion (including the experts who would have accepted TOP at the outset and those who would have accustomed it in the light of clinical progression), as this is the merely figure that is comparable with the literature data and real-life situations.

We submitted the three online clinical cases using www.evalandgo.com to 30 prenatal diagnosis experts in the x PDCs in the Paris-Île de France region. The contacted members received a link to answer the survey. The vignettes were presented as clinical cases. Questions were asked progressively and depending on the answers. If the person answering the questionnaire agreed with TOP in the first identify, he would exist directed to the next vignette. If he answered he refused TOP, the clinical case was continued.

In each PDC, we asked an attending obstetrician-gynecologist, an attention pediatrician and a cytogeneticist or geneticist. Other professionals work in these PDCs, and the center's final decisions includes the opinions of all participants, including midwives, fetal pathologists, obstetrician-gynecologists other than the attending obstetrician-gynecologist, pediatricians other than the attention pediatrician, etc. To optimize recording of the decisions taken by the PDCs, we decided to question members exhaustively in two centers. So, we submitted the aforementioned three clinical cases to all staff members in these ii PDCs, including all obstetrician-gynecologists, pediatricians, geneticists, cytogeneticists, midwives, sonographers and fetal pathologists.

For each clinical instance, we calculated the percentage of agreement to accept the asking for TOP, the percentage of agreement to turn down Peak and the percentage of disagreement. Nosotros did so using the method initially described by Chamberlain [33] and later on generalized by Grant [34] to tests for more than than two observers.

We asked 30 experts. Nosotros obtained 27 fulfilled questionnaires. We calculated the agreement amongst observers in favor of accepting a request for Peak equally e = northwardi (northi– 1)/2 where ni was the number of experts who thought Top was justified and thus said "yes" to Elevation in the online questionnaire. We calculated understanding to refuse a request for Acme equally g = mi (mi– 1)/2 where mi was the number of experts who idea that a TOP was non justified. Then we calculated the sum of understanding to accept TOP for all the vignettes as \( \mathsf{C}\mathsf{ifor}={\sum}_3^1e \) and the sum of agreement to pass up TOP as \( {C}_{iagainst}={\sum}_3^1g \). Disagreement concerning a decision for Acme was alculated as \( f=\frac{\left(\left({n}_i+{one thousand}_i\right)\ast \left({northward}_i+{m}_i-one\correct)\right)}{2}-e-chiliad \). Sum of disagreement was calculated as \( {D}_i={\sum}_3^1f \) (Boosted file 1: Table S1). Percentage of agreement to have a request for TOP was calculated every bit \( {P}_{accept}=\frac{C_{ifor}}{\left({C}_{iagainst}+{C}_{ifor}+{D}_i\correct)} \). Per centum of agreement to refuse a request for TOP was calculated every bit \( {P}_{decline}=\frac{C_{iagainst}}{\left({C}_{iagainst}+{C}_{ifor}+{D}_i\right)} \).

Percentage of disagreement was calculated equally \( {P}_{disagree}=\frac{D_i}{\left({C}_{iagainst}+{C}_{ifor}+{D}_i\right)} \).

We also used a multi-level (hierarchical) logistic regression analysis in order to test the possible consequence of specialty on decisions of experts to have (or not) a request for Peak. We used a multi-level model in order to take into business relationship the hierarchical cases (vignettes) nested within experts (of dissimilar specialties), in turn nested within centers.

For the understanding analyses we used Excel (Microsoft Office, version 15.0.4737.1003). For the multilevel model, we used the multilevel logistic model (melogit) of Stata software (Stata 13.1, Texas, The states).

This study was canonical by the Upstanding Review Committee « Comité d'éthique de la recherche en obstétrique et gynécologie » under the number CEROG OBS 2017-02-26. This research was constitute to conform to generally accepted scientific principles and medical enquiry upstanding standards by the upper stated institutional review lath.

Results

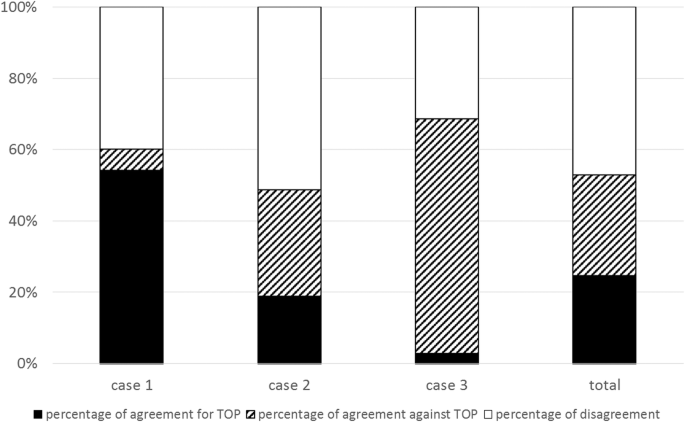

We received 27 responses from the 30 experts in the 10 PDCs. For the first clinical case (discovery via nuchal translucency), the percentage of agreement to take TOP was 54% and the percentage of agreement to refuse TOP was 6%. For the second clinical instance (serendipitous discovery), the per centum of agreement to take and to refuse TOP were respectively, nineteen and 30%. For the third case (discovery considering of aortic coarctation), the corresponding percentages were 3 and 66% (Fig. 2). For the three clinical cases taken together, the pct of agreement to accept TOP was 25%, the percentage of understanding to refuse 28% and the percentage of disagreement was 47% (Fig. 2).

Percentage of agreement to have a request for termination of pregnancy (Pinnacle), agreement to turn down a asking for TOP and disagreement in the 10 prenatal diagnosis centers

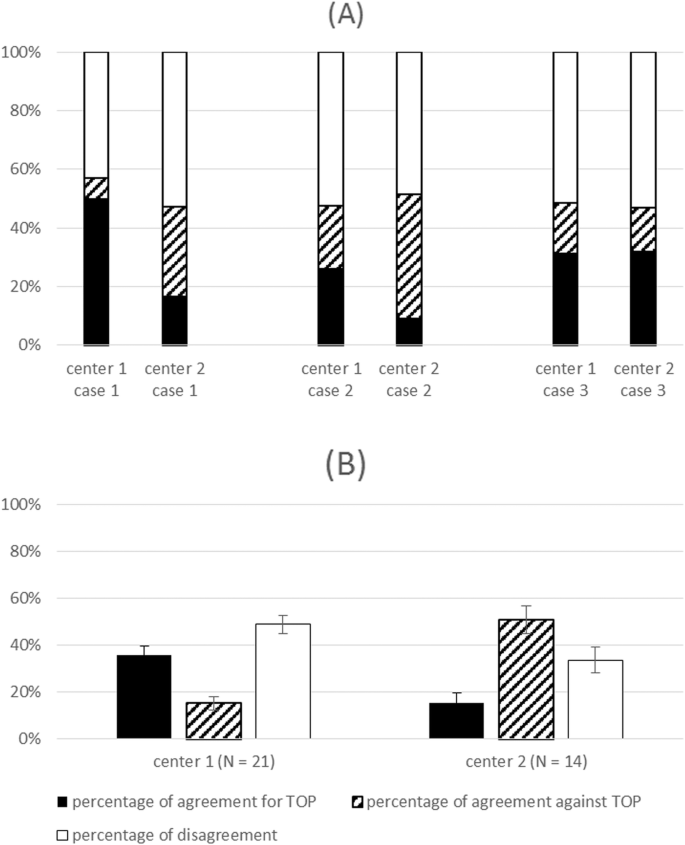

In the two centers where we questioned all staff members, we obtained 21 responses in center 1 (9 gynecologist-obstetricians, four pediatricians, 2 sonographers, 1 midwife, 1 anatomic pathologist, one geneticist and 2 cytogeneticists) and 14 responses in middle 2 (6 gynecologist-obstetricians, 3 pediatricians, 2 sonographers and 3 cytogeneticists). The percentage of agreement to accept TOP was for cases ane, 2 and three, respectively, l, 26 and 31% in center 1 and 16, 7 and 32% in center 2. The overall results for the 3 cases are shown in Fig. 3.

Percentage of agreement to take Top, agreement to refuse TOP and disagreement in centers 1 and 2. a Percentages instance by case. b Overall percentages for the iii cases. The error bars stand for the 95% confidence intervals. Blackness: per centum of understanding to take TOP. Diagonal lines: pct of agreement to pass up Height. White: percent of disagreement

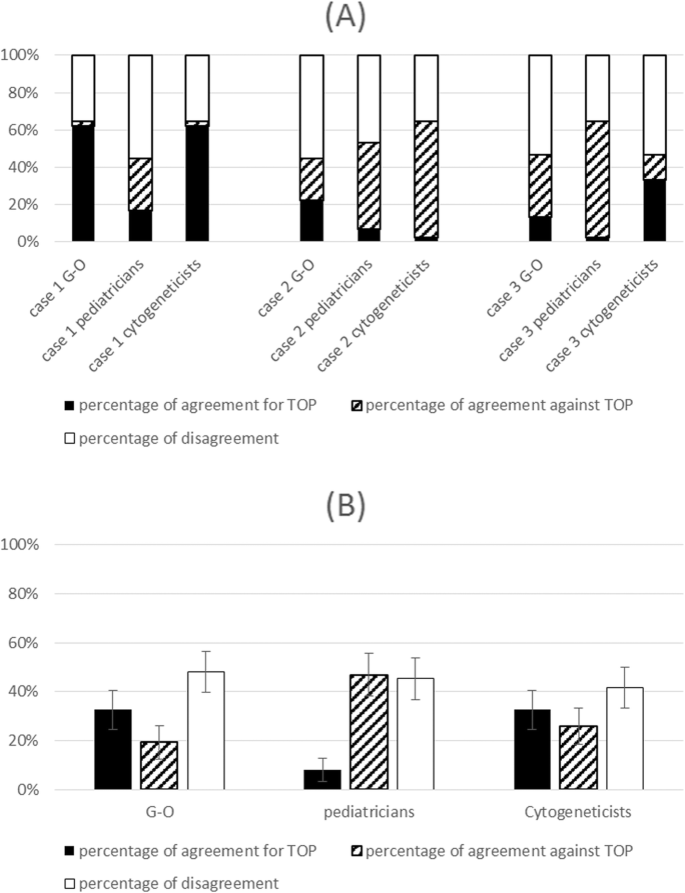

In Fig. four, we show results inside each of the three specialties. The overall percentages of agreement (for the three cases together) to accept Summit were, respectively, 33, 8 and 33% for gynecologist-obstetricians, pediatricians and cytogeneticists (Fig. 4). The percentage of understanding to decline TOP was, respectively, xix, 47 and 26% (Fig. four).

Percentage of agreement to accept Top, agreement to pass up Height and disagreement by profession (obstetrician, pediatrician, cytogeneticist). a Percentages instance by case b Overall percentages for the iii cases. Chiliad-O: gynecologist-obstetricians

Our multilevel model shows that the variance of the centre was 0.32 (95% CI: 0.06–one.76) and that of the experts 0.05 (95% CI 0.000001–2205). There was a significant effect of the center (level 3) and of the experts (level 2).

The results of the multilevel, multivariate assay for the terminal decision to approve TOP are presented in Table 1. In that location was no meaning difference among specialties in univariate or in multivariate analysis.

Discussion

Prenatal counseling after diagnosis of Turner syndrome is complex. The risk of intellectual disability is low (6 to 10%), only may seem unacceptable to some parents. Other issues like infertility and long-term medical complications lead parents to request TOP following sometimes serendipitous prenatal discovery of Turner syndrome. Nonetheless, the members of PDCs may not have the same perception of these postnatal complications and may not accept this asking. Overall, we found lack of consensus regarding option of Top for Turner syndrome; this was reflected in both the percentages of disagreement among experts and in the low percentages of agreement to accept or to decline TOP. Our results bear witness differences in the experts' decisions depending on the mode of discovery of Turner syndrome and associated ultrasound findings: higher percentages of agreement were found when Turner syndrome was diagnosed on increased nuchal translucency, whereas higher percentages of disagreement were institute when Turner syndrome diagnosis was serendipitous. Morover, variations can besides peradventure be explained past the gestational historic period of diagnosis of Turner syndrome. Indeed, as shown Fig. ii, higher per centum of agreement against TOP were institute for case 3, when Turner syndrome was diagnosed during the third trimester of pregnancy. Finally, at that place appeared to be a specialty effect with pediatricians accepting less oft a TOP request even if most probable due to low power this association was non statistically significant. Indeed, this report lacks of sample size calculation. We transport the survey to all the Prenatal Diagnosis Centers in the Parisian region. We contacted 1 obstetrician, ane pediatricien and one genetician in each middle. All except three ansered to the survey.

The opinion of the experts in this report seems to differ from the situation in existent life, where approximately 78% of pregnancies are terminated when Turner syndrome is diagnosed, according to the Paris Registry of Congenital Malformations [35]. In our study there was 72% agreement to accept TOP, which corresponds to merely 48% of Acme which would have finally been accepted (cf Figs. 2 and 5). There are several possible explanations for the mismatch between our results and real-life findings. First, our written report differs from what is seen in practice. Real-life follow-up may include other aspects, notably ultrasound signs not found in our clinical cases. Such signs can besides contribute to acceptance of TOP, particularly if they worsen the prognosis. Likewise, having met the parents, the experts will exist particularly sensitive to their request. Their position volition be influenced by the particular situation of the parents, whereas other members of the PDC will be more than neutral and will talk over the indication for TOP on a theoretical basis. Experts' decisions in this survey were not influenced past the pressure level usually fabricated by couples requesting TOP and their caring practitioners. Indeed, the doctors who met the parents usually play an important function in the final decision-making within the PDC. Morover, variations in the population served in unlike PDCs could influence decisions of some PDCs beyond the police. Cultural and ethical differences influence the number of requests for TOP and hence the caregivers might be more willing to accept Superlative within populations who asking it more than rarely.

Comparison between our study data (DAGO) and the Paris Registry of Built Malformations 2008–2012

In fact, the sum of the percentage of agreement to approve TOP and the pct of disagreement were highly comparable to the observed percent of Acme in registries (cf Fig. v). The conclusion by PDC members to accept TOP for Turner syndrome is therefore not necessarily unanimous. It is nearly probable that a Tiptop is accepted inside PDCs either if members of a PDC unanimously accept the parents' request for TOP, or either if some members accept information technology. Indeed, the last situation is in accordance with the police force in France every bit long equally two specialist members of the PDC recognize the incurability and seriousness of the case [30]. The construction of the PDCs is thus designed to guarantee the best possible match between the parents' request and the law, by accompanying the PDC's decision with an interpretation of the individual perception. This over-representation of Elevation for Turner syndrome in registries may also be related to how information was get-go given to the parents. The initial information has a major touch on on the parents' last determination. Sometimes the parents are informed of the results of fetal karyotyping by a health intendance worker who does not actually know the prognosis of Turner syndrome. In this regard it is essential to optimize in each PDC how and past whom the parents are told of the karyotyping outcome. The announcement should be made by the specialist in the illness and its prognosis, and a consultation with an endocrinologist-pediatrician and a cytogeneticist should be arranged without filibuster.

We practise not think it will be possible to clarify guidelines for prenatal prognosis of Turner syndrome as it will ever correspond a broad phenotypical spectrum. Neither practice we promise to take a limited list of fetal pathologies for which Elevation seems to be acceptable. However, serendipitous diagnosis of Turner syndrome will probably be more frequent with the growing use of non invasive prenatal diagnosis. Hence the results of this report insist on PDCs' role to avoid a drift of decisions towards inadequate or hasty decisions of Top especially in a country were TOP is allowed at any gestational age.

Conclusions

We found a low percentage of agreement for Pinnacle for Turner syndrome, and lower than what is observed in real life. Differences among members of PDCs are highlighted by high percentages of disagreement. This report illustrates the complexity attendant upon decisions relating to termination of pregnancy in cases of Turner syndrome. It witnesses the ethical tensions linked with these decisions; in detail for Turner's syndrome without anomalies on the obstetrical ultrasound scans. The multidisciplinary organization of prenatal diagnosis centers is determinant in meeting requests for termination of pregnancy, considering both the disease and the parents' characteristics. The knowledge of these differences might influence the organisation within PDC related to the way the data is given to parents apropos invasive and noninvasive procedures which could lead to a serendipitous discovery of the anomaly.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this commodity are available upon asking to the corresponding writer.

Abbreviations

- DAGO:

-

Antenatal Diagnosis of Gonosomal Abnormalities

- PDC:

-

Prenatal Diagnosis Eye

- TOP:

-

Termination of Pregnancy

References

-

Cabrol S. Turner syndrome. Ann Endocrinol. 2007;68(1):two–nine.

-

Cabrol Southward, Saab C, Gourmelen Grand, Raux-Demay MC, Le Bouc Y. Turner syndrome: spontaneous growth of stature, weight increase and accelerated bone maturation. Arch Pediatr. 1996;three(four):313–eight.

-

Ranke MB, Pfluger H, Rosendahl W, Stubbe P, Enders H, Bierich JR, et al. Turner syndrome: spontaneous growth in 150 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 1983;141(2):81–8.

-

Linglart A, Cabrol South, Berlier P, Stuckens C, Wagner K, de Kerdanet Thou, et al. Growth hormone treatment earlier the age of four years prevents short stature in young girls with turner syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164(6):891–7.

-

Price DA, Ranke MB. Growth hormone in turner syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84(6):525.

-

Ranke MB. Why treat girls with turner syndrome with growth hormone? Growth and beyond. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2015;12(iv):356–65.

-

Ross J, Lee PA, Gut R, Germak J. Impact of age and duration of growth hormone therapy in children with turner syndrome. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;76(half dozen):392–nine.

-

Bruandet M, Molko Northward, Cohen L, Dehaene S. A cerebral characterization of dyscalculia in turner syndrome. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42(iii):288–98.

-

Collaer ML, Geffner ME, Kaufman FR, Buckingham B, Hines 1000. Cognitive and behavioral characteristics of turner syndrome: exploring a office for ovarian hormones in female person sexual differentiation. Horm Behav. 2002;41(2):139–55.

-

Ross JL, Stefanatos GA, Kushner H, Zinn A, Bondy C, Roeltgen D. Persistent cognitive deficits in adult women with turner syndrome. Neurology. 2002;58(2):218–25.

-

Ranke MB, Saenger P. Turner's syndrome. Lancet. 2001;358(9278):309–xiv.

-

Ankarberg-Lindgren C, Elfving G, Wikland KA, Norjavaara Eastward. Nocturnal application of transdermal estradiol patches produces levels of estradiol that mimic those seen at the onset of spontaneous puberty in girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(7):3039–44.

-

Bannink EM, Raat H, Mulder PG, de Muinck Keizer-Schrama SM. Quality of life after growth hormone therapy and induced puberty in women with turner syndrome. J Pediatr. 2006;148(1):95–101.

-

Bannink EM, van Sassen C, van Buuren S, de Jong FH, Lequin M, Mulder PG, et al. Puberty induction in turner syndrome: results of oestrogen handling on development of secondary sexual characteristics, uterine dimensions and serum hormone levels. Clin Endocrinol. 2009;70(ii):265–73.

-

Piippo S, Lenko H, Kainulainen P, Sipila I. Apply of percutaneous estrogen gel for consecration of puberty in girls with turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(seven):3241–7.

-

Saenger P, Wikland KA, Conway GS, Davenport Yard, Gravholt CH, Hintz R, et al. Recommendations for the diagnosis and management of turner syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(7):3061–9.

-

Donadille B, Rousseau A, Zenaty D, Cabrol Due south, Courtillot C, Samara-Boustani D, et al. Cardiovascular findings and management in turner syndrome: insights from a French cohort. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167(4):517–22.

-

El-Mansoury Chiliad, Barrenas ML, Bryman I, Hanson C, Larsson C, Wilhelmsen L, et al. Chromosomal mosaicism mitigates stigmata and cardiovascular adventure factors in turner syndrome. Clin Endocrinol. 2007;66(5):744–51.

-

El-Mansoury M, Bryman I, Berntorp One thousand, Hanson C, Wilhelmsen L, Landin-Wilhelmsen K. Hypothyroidism is common in turner syndrome: results of a five-year follow-upward. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(4):2131–5.

-

Elsheikh Thousand, Wass JA, Conway GS. Autoimmune thyroid syndrome in women with Turner'due south syndrome--the association with karyotype. Clin Endocrinol. 2001;55(2):223–6.

-

Landin-Wilhelmsen Chiliad, Bryman I, Windh G, Wilhelmsen L. Osteoporosis and fractures in turner syndrome-importance of growth promoting and oestrogen therapy. Clin Endocrinol. 1999;51(four):497–502.

-

Mikosch P, Gallowitsch HJ, Kresnik E, Lind P. Osteoporosis in Turner syndrome with chromosomal mosaicism (45,XO/46,XY). A instance report. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2000;150(12):262–five.

-

Rubin 1000. Turner syndrome and osteoporosis: mechanisms and prognosis. Pediatrics. 1998;102(2 Pt 3):481–5.

-

Perrotin F, Guichet A, Marret H, Potin J, Body M, Lansac J. Prenatal outcome of sex chromosome anomalies diagnosed during pregnancy: a retrospective study of 47 cases. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2000;29(7):668–76.

-

Boyd PA, Loane Thousand, Garne E, Khoshnood B, Dolk H. Group Ew. Sex chromosome trisomies in Europe: prevalence, prenatal detection and event of pregnancy. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(two):231–four.

-

Brun JL, Gangbo F, Wen ZQ, Galant K, Taine L, Maugey-Laulom B, et al. Prenatal diagnosis and management of sexual activity chromosome aneuploidy: a report on 98 cases. Prenat Diagn. 2004;24(3):213–viii.

-

Christian SM, Koehn D, Pillay R, MacDougall A, Wilson RD. Parental decisions following prenatal diagnosis of sex chromosome aneuploidy: a trend over time. Prenat Diagn. 2000;20(1):37–xl.

-

Garne East, Khoshnood B, Loane M, Boyd P, Dolk H, Group EW. Termination of pregnancy for fetal anomaly afterward 23 weeks of gestation: a European register-based study. BJOG. 2010;117(half-dozen):660–six.

-

Abortion. Legislation in Europe. IPPF. International Planned Parenthood Federation, updated january 2012. https://www.ippfen.org/sites/ippfen/files/2016-12/Final_Abortion%20legislation_September2012.pdf. Accessed Jan 2012.

-

Recommandations Professionnelles de l'Agence de la Biomédecine pour le fonctionnement des Centres Pluridisciplinaires de Diagnostic Prénatal (CPDPN). Agence de la Biomédecine, 2012. https://world wide web.agence-biomedecine.fr/IMG/pdf/recommandations_cpdpn2013.pdf. Accessed Dec 2012.

-

Khoshnood B, de Vigan C, Vodovar V, Goujard J, Lhomme A, Bonnet D, et al. Trends in antenatal diagnosis, pregnancy termination and perinatal mortality in infants with congenital heart disease: evaluation in the general population of Paris 1983-2000. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2006;35(5 Pt 1):455–64.

-

Gruchy N, Vialard F, Decamp M, Choiset A, Rossi A, Le Meur N, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in 188 French cases of prenatally diagnosed Klinefelter syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(9):2570–5.

-

Chamberlain J, Rogers P, Price JL, Ginks S, Nathan BE, Burn I. Validity of clinical examination and mammography equally screening tests for chest cancer. Lancet. 1975;two(7943):1026–30.

-

Grant JM. The fetal centre charge per unit trace is normal, isn't it? Observer agreement of chiselled assessments. Lancet. 1991;337(8735):215–8.

-

Khoshnood B, De Vigan C, Vodovar V, Goujard J, Lhomme A, Bonnet D, et al. Trends in prenatal diagnosis, pregnancy termination, and perinatal mortality of newborns with congenital heart disease in France, 1983-2000: a population-based evaluation. Pediatrics. 2005;115(1):95–101.

Acknowledgments

We give thanks the scientific committee (Olivia Anselem, Claire Bouvattier, Agnès Choiset, Aurélie Coussement), which helped elaborate the clinical cases. Nosotros also give thanks all PDC members who responded to the online clinical cases.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

MH, OA, CB, AC, AB and VT helped elaborate the clinical cases presented equally vignettes in the present study. BK, VT and MH elaborate the methodology of this written report. MH and BK performed the statistical analyses. MH wrote the first typhoon of the manuscript. BK, OA, AC, SB, CB, AB and VT made substantial revisions to the drafted manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ideals declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This written report was approved by the Ethical Review Committee « Comité d'éthique de la recherché en obstétrique et gynécologie » nether the number CEROG OBS 2017-02-26. This research was found to accommodate to generally accepted scientific principles and medical inquiry ethical standards by the upper stated institutional review board. Participants were invited to participate through the online survey. They could cull to participate or not. Information concerning the possibility to participate or not, what the information would exist used for and how it would be used was included in the data concerning the survey before starting to answer. Consent to participate corresponded to answering the survey. This maner of displaying the information was approved by the Ethical Review Committee.

Consent for publication

Non applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they accept no competing interests.

Boosted data

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary data

Rights and permissions

Open Admission This commodity is distributed nether the terms of the Artistic Eatables Attribution four.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/past/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original writer(south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/i.0/) applies to the information made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Nigh this article

Cite this commodity

Hermann, M., Khoshnood, B., Anselem, O. et al. Lack of consensus in the choice of termination of pregnancy for Turner syndrome in France. BMC Health Serv Res xix, 994 (2019). https://doi.org/x.1186/s12913-019-4833-3

-

Received:

-

Accustomed:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12913-019-4833-3

Keywords

- Sex chromosome anomaly

- Termination of pregnancy

- Turner syndrome

- Vignette study

Source: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-019-4833-3

0 Response to "What Percent of Turners Babies Make It After 2nd Trimester of Pregnancy"

Post a Comment